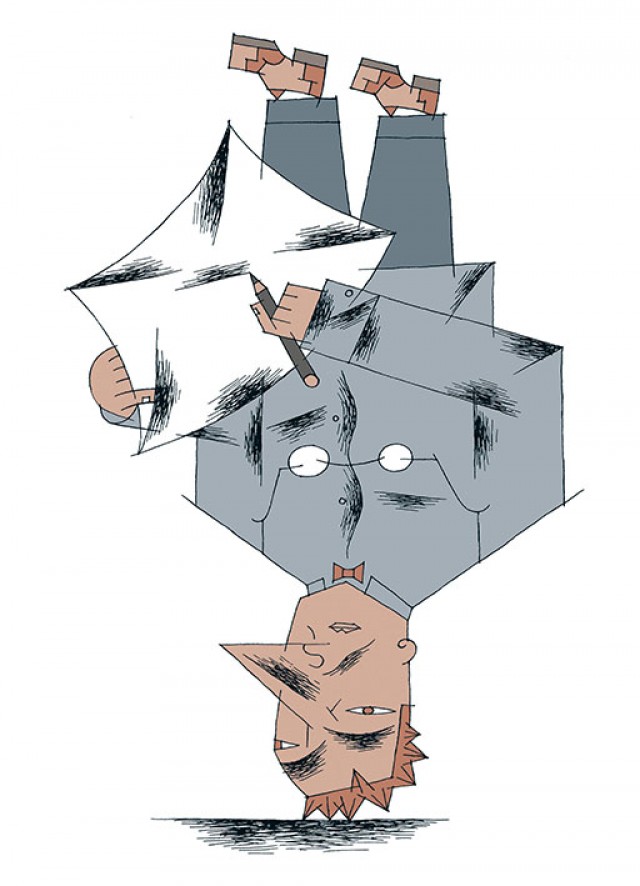

Calatayud, Miguel

Dear boys, dear girls, now that you have gotten to know the world upside down you will have noticed that it is a world very similar to ours. Sometimes things do not work out so well: more people die from the bite of a tiny mosquito than from the bite of a tiger; useless things are usually the most expensive; we humanise machines while humans become more and more like machines.

The artist who has portrayed this world, which is so similar to ours, even while being upside down, is called Miguel Calatayud.

As a young boy, Miguel watched many films and read many books. Since there are many people who barely read a thing, some have to read for two. Some children have their bedroom plastered with a pretty illustrated wallpaper that becomes the backdrop for their adventures and games; other children live their life of dreams inside that wallpaper. Miguel was one of those children.

If he had been born a few years earlier he might have ended up painting impressive bisons, agile deers, or accurate archers on cave walls. While artists were inventing the first painting without paper, the hunters chased behind prehistoric rabbits, and sometimes ran in front of prehistoric cows, foreshadowing the Festival of San Fermín. Since then, the world has gone round many times, it never stops spinning; and yet, we are unaware of where it is headed.

If Miguel Calatayud had been born a few spins later, he could have been the neighbour of the famous Florentine painter Paolo Uccello; together, they would have climbed onto a roof to draw people from above and perfect the invention of perspective. People, seen from above, have big heads and short legs, and they look squashed against the ground like a trail of ants.

Some other spins later, Miguel could have met Francisco de Goya, another famous portrait painter of the upside down world. They would have had great conversations about the divine and the humane with a glass of red wine in their hands.

The caveman mainly searched for magic effects in his paintings: he wanted to guarantee a good hunt and a good harvest; Uccello, ‘the bird’ (this is what uccello means in Italian), wished to represent through colour and geometry the world as it is and bear witness of its order; Goya searched for meaning in the world: he looked around and immediately found things that did not work very well, to say the least. Instead of writing complaint letters with no recipient address, he created for his peers one of the most famous series of prints, which he called ‘whims’.

Absurdity, senselessness, and whims, as Goya knew and Miguel knows, form part of our lives. The world upside down, dear boys and girls, dresses up every day in a different disguise. We can all find examples of things that do not work very well, to say the least. We can get serious and denounce that there are super rich people when there are still those who are super poor, and ask ourselves what would happen if animals rebelled against us, their cruel masters; or we could, jokingly, play at flipping everyday situations and speak ‘upside down’ and think ‘upside down’, to see if we like the result better.

After reading this book by Miguel Calatayud which says so much in so few words, and which also has the advantage that it can be opened at any page, we will have earned the world upside down’s exploring licence and we will be able to go out and put in practice our recently acquired skills. As soon as we step out on the street, what do we see?: we see an ambulance passing by, blaring its siren; and on the ambulance’s sign, what do we read?:

Herrín Hidalgo