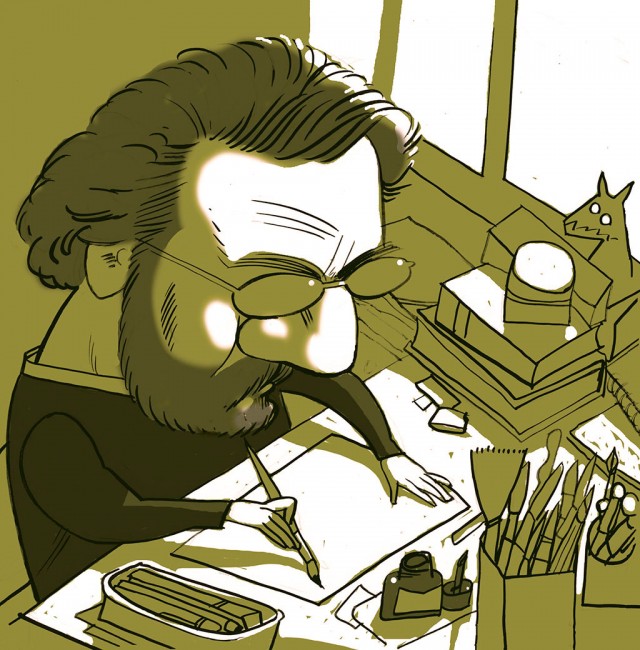

Cano, José Luis

José Luis Cano (Zaragoza, 1948) is an individual and a multitude. This is why it is so difficult to know who the man is signing José Luis Cano, or just Cano, or Canico, as he is also known, because he makes ‘canicos’: almost minuscule books where he encloses, in few pages, scarce words and abundant illustrations, as well as illustrious, illustrated, and illuminated lives.

He probably has the world’s most stentorian laugh, loud as a raging torrent, disobedient as an untamed foal. Some say that he looks like he could be El Roto’s twin brother, but their main difference, above all, is that Cano laughs better and more often. His laugh is almost wild, which is the obverse of a shyness so abrupt as it is well-managed. And like Andrés Rábago ‘El Roto’, he is bright, radical, takes life by the reins and summarises it in a speech bubble that resembles a thought by Cioran.

José Luis Cano began drawing comic strips in the early 1980s. Being an expressionist artist, he created caricature men with huge horns, his personal approach to cubist caricatures, and grandmas who were not much more than a mourning triangle and a ‘black smear with a nose and legs’. These and many more characters spoke, using subject and predicate, like philosophers: they put into orbit what has been referred to as ’somarda humour’ (a type of humour specific to the region of Aragon), that mixture of natural anarchy, stupidity, and popular wisdom that causes havoc. They say things as if they do not wish to say them, and leave you with an ache in your stomach and intelligence. Later, nearing the 1990s, Cano chose two other characters: a rural elder from a tribe hugging a sheep, who is quite bitter about everything (even about the whims of the seasons), and a woman with a radio that vomits news nonstop. The radio frustrates the listener or helps them to understand the world. Deep down, Cano has always been preparing the staging of his great sense of humour, which would have its absolute projection on a vast handful of characters from Aragon marked by a common trait: schizophrenia.

He has dedicated a recent book to this matter, and some of those creatures reappear here, in this trip to Zaragoza through time: from San Lamberto to the drawer Gutiérrez, who drew a portrait of Gregorio Calmarza; from Engracia and Avempace to Francisco Marín Bagüés, who wanted to paint a mural in El Pilar that never happened. While overseas, Goya kept saying: ‘When I think of Zaragoza and painting, I burn alive’. Although my favourite character is the least known: María Luisa Cañas, Marisica. This real anecdote fits Cano perfectly. He hates happy endings. He could never be a best-seller.

Zaragoza is one of the cities with the most illustrious and rare characters per square metre. Cano is one of them, and here, he sees them all as equals: as ancestors with familiar traits, as brothers, accomplices, and as mad men. To some he had dedicated complete monographs under the Xordica Publisher seal (Buñuel, Goya, María Moliner, Gracián, Sender, Ramón y Cajal, Ferdinand II of Aragon…), but he does not repeat himself. In addition, he achieves something admirable: he transforms Zaragoza into the centre of outstanding lives, into the stage of anecdotes, rebellions, and surrealist or cruel gestures such as the death of St. Dominguito del Val. He also knows how to transform an isolated instant, like the portrait of Ava Gardner by Luis Mompel, into a story, an adventure with value in itself, into a legend about love at first sight in a bullring. José-Carlos Mainer once said that the writer José Luis Cano was close to the erudition and the spirit of Borges. Cano is a storyteller, a visual poet, an alchemist of pencil strokes, the Spanish relative of David Levine. Only someone like him could think that Eusebio Blasco deserves immortality for inventing the term ‘suripanta’ (a derogatory term referring to immoral women or women who form part of a theatre choir).

Antón Castro