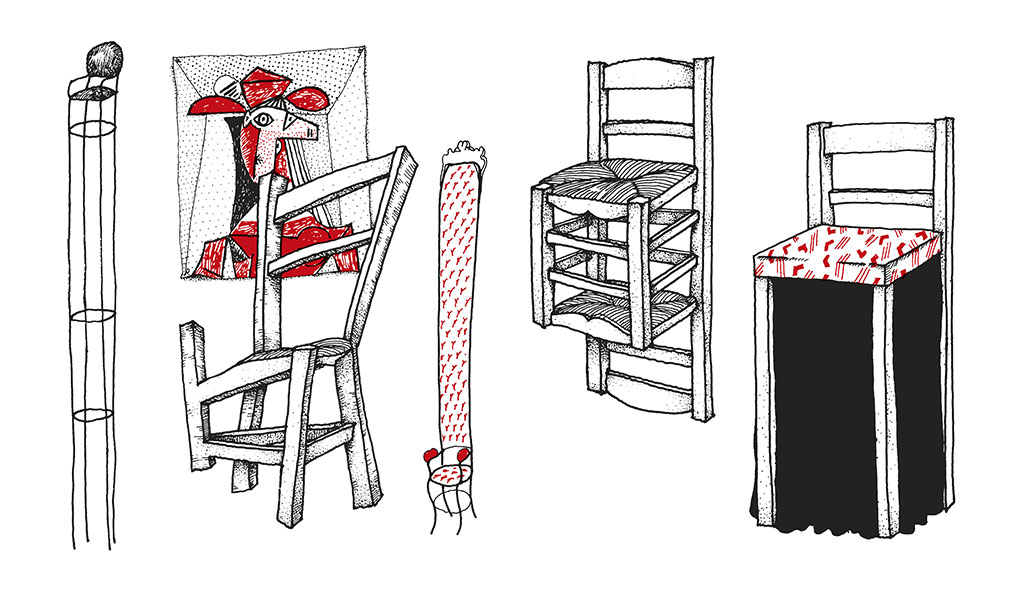

The illustrator as a piece of furniture

This chair

My grandfather, the Baron of Chlussowiez, was a great artist. He learned to paint by copying Brueghel’s prints and portraits of saints with annoyed expressions. He would go into the forest and come out after a while as a bush, carrying a collection of twisted roots which he shaped into a bird. He used egg shells to made their eyes.

For some time he only painted trees. And found out that whatever he put on paper continued to be a tree even if he plucked off the leaves, or removed the trunk and branches. It was a pine, or a cypress, or a willow, or a carob tree, but it was nothing more than two drops of coloured water.

He went on outings with his painter friends and, sitting in the shade of an oak tree in the town square, one day during a procession they competed to see who could draw more altar boys. When the painting was finished, they tallied up.

My grandfather the baron, when he was not painting in the forest or on a town bench, he painted in a room in his city house, which he had arranged to make it comfortable for him. In that room he had a slanted desk with an adjustable lamp and a swivel chair that allowed him to access the drawing utensils spread across the desk, and to change his posture from time to time.

After my grandfather passed away, as a way to remember him, I received, not the paintings, nor the desk, nor the lamp, nor his folders, but the chair. The chair from which I am writing now, and which represents, as no other object, the very shape and essence of illustrators.

From the cradle to the grave

The illustrator Norman Rockwell has portrayed himself on countless occasions. ‘From the Cradle to the Grave’ is a sequence of drawings that showcases the author in different stages of his life.

Early on, baby Norman clenches paper and pencil in his fists and begins to sketch his first cover for the Saturday Evening Post. From the canvas ceiling of the cradle peeps out the pipe that will be linked to the author’s most distinctive image.

Throughout his life, Rockwell portrays himself backwards, drawing on an easel, with the pipe poking out from behind his head. He only changes from one seat to another.

From the cradle he leaps to a high stool. From there, he moves to a swivel chair. Now in his sixties, he needs a wide armchair with all four legs firmly anchored in the ground. In his mid-nineties, he draws (in a Cubist style) from the inside of a coffin.

He is not there in the last drawing: all we see is a slightly tilted tombstone, and the pipe, of course, peeping out of the subsoil.

Progress

Illustrators, their classic form: sat on their chair, leaning over their drawing desk like the farmer over the ground. Their sun is the lamp’s light, the nib pen their plough, and, instead of a horse or a dog, they have a cat nearby.

Looking at it this way, it could be said that the invention of computers has been to illustrators what tractors were to farmers.

Planes

I perfectly remember visiting with a friend, in our long gone adolescence, the study of a famous illustrator.

The illustrator showed us the latest projects he was working on, and we were able to touch his originals and see the boxes of paints and the reference books he had open on the table. In short, all those things that make enthusiasts go crazy.

In such circumstances, the mentor is asked for some secrets of the profession, for a wonderful tip on what type of brush would be best to use for drawing smoke, or for the exact shade of red to give indigenous people’s skin.

None of this mattered much to me, but I remember there was something I wanted to ask the famous illustrator: ‘Do you draw on planes?’ I also remember the artist’s shocked face.

For me, at that moment, drawing was not worth the while if one could not do it on planes. A famous person was someone who travelled by plane, so an illustrator had to be someone curious and restless who could draw anywhere. Ah, sweet adolescence.

Attics

This year, 1998, is the 400th anniversary of the birth of the inventor of attics. The newspapers are talking about it. I think it is appropriate to quote the architect François Mansart (1598-1666) because we illustrators should also pay him tribute.

Illustrators search penthouses and attics as ideal habitats because their permanent aspiration is to gain light and height. Light is everything to artists: it is the main ingredient of any of their dishes. The light that comes through the window of the attic illuminates the brain of the building and of those who live in it. Height is necessary to widen the field of vision and dominate everything. Artists, creators, climb the mountain and stand in the ‘eye of God’ to contemplate the entirety of their creation.

There are also illustrators who live in penthouses simply because these are the places cats prefer. The illustrator Lorenzo Goñi is a portraitist par excellence of that mysterious life that takes place at night in attics.

Ultimately, an attic is a type of plane. So it is true, one can draw on planes. Even if one travels exclusively with the imagination.

In a hundred years’ time

It seems logical to think that all drawings will have been made by then (Finally! About time!) and there will be large image catalogues available to everyone. There will be no illustrators, or we will all be illustrators. People will communicate through images as we now do through writing. One will be able to choose words or select images from a vast repertoire, and, depending on one’s mood, write a novel or paint a picture.

It also seems logical to think that specialised illustrators will continue to exist, although they will have pushed the plough and tractor aside and begun to dictate drawings into a machine just like texts are being dictated now: ‘A Crepax-like nose at coordinates x=59,82225; y=71,18905’.

There is a third possibility, which is no less logical and no less absurd: in a hundred years’ time, perhaps there will only be a reduced community of illustrators on Earth, survivors of the floods that will devastate the planet. Due to melting icecaps, the sea levels will rise and many cities will disappear under water. Only a few illustrators will remain, because they live in attics.

Phileas Fogg

It would seem logical to think that in a hundred years illustrators will have freed themselves from the chair that chains them to the desk and from the desk that only serves to rest the paper, and even from the paper itself, which is a material that tends to disappear even from bathrooms.

All the furniture will end up in the ravenous cauldron that keeps this civilising fever going, and will end up as thinned out as the structure of the ship dismantled by Phileas Fogg during his trip around the world in eighty days.

If the predictions of the visionary Professor P. Pacetti prove to be true, in 21st century homes, the control over gravity will allow humans to access every corner of a house, even those where hairy spiders hang their hammocks. The houses could be made of straw, planks, or bricks, like those of the Three Little Pigs; or of some unknown material; or of cheese or chocolate; but they will not have much furniture. Each individual will hold in themselves all the furniture. If one can sit on air, why do it on a chair?

To be furniture

Illustrators are writers who write with images. They are people who organise the materials they work with in a specific way to give them meaning. These ‘materials’ often refer to things as intangible as ideas. Then there is style, the particular way in which each person presents those materials, those ideas.

Jules Renard wrote: ‘To think is not enough, you must think of something’. For this reason, it is essential to move. It is essential to have our heads well furnished and move the pieces once in a while.

To be furniture. To be that which moves and not that which is still. Professionals in the world of illustration must move, and not necessarily by plane or by surfing the Internet. Illustrators must demand and assume their responsibilities as authors, placing themselves above the strict fulfillment of a commission and becoming an honest witness of the times they live in.

In other words, to draw is not enough. One must draw something.

This exhibition

Sitting on my grandfather’s swivel chair, I spin round and round and the outlines of the objects begin to blur until everything around me disappears. This is another advantage of swivel chairs when they are well greased: they allow you to travel through time.

So, three illustrators who share a study, will drink coffee from the same flask and eat the same sandwiches, but while one travels in his chair to the Mayan constructions of Chichén Itzá, another goes to the Italy of Leonardo, and the third to New York in the 1960s, and takes the opportunity to visit Saul Steinberg.

I have travelled to the future and peeked beyond the year 2050. I am not sure what I am seeing exactly, among other things because I have landed in the middle of Africa and in this place, as in so many others, calendars are disrupted; but I am going to stroll around this exhibition with my eyes wide open to learn something from the collection of looks, as well as to admire the bold proposals of those who enter forests to look for roots and come out carrying birds. And they fly.

The art of living

Saul Steinberg, a man very much like my grandfather, who happens to be one of the most influential contemporary illustrators, has evidently drawn many chairs and armchairs.

One of his first books, The Art of Living (1949), he devotes the first pages to chairs and to the thousand ways one can sit on them. Further on, however, when he presents an illustrator at a desk, he does so without a chair. The illustrator is part of the drawing, the head continues into the hand, the hand extends into the pencil, the pencil traces lines on the desk, these lines suggest a horizon, and on this horizon buildings, cars, and urban agglomerations are placed.

The scene will close, logically, with the drawing of the chair that does not yet exist and which completes the illustrator.

Vicente Ferrer Azcoiti