Rhymers eulogy

First of all, I would like to thank my friends at Ekaré for inviting me to present this Chamario by Eduardo Polo and Arnal Ballester. They have no idea what they have done by inviting the competition to present your book. In a publishing market that tends to value production and promotion exclusively from a business perspective, such a gesture demonstrates a high spirit I particularly appreciate.

I have known Arnal Ballester, the illustrator of Chamario, for a long time and I would like to tell you how we met. That long time has a date: April 1994. Arnal had just won the National Illustration Award in 1993 for the book La boca riallera, and the CLIJ magazine had asked him to write a self-portrait. This is the final text published in the magazine:

In one of Saski’s stories, a traveller tells a story to a group of fussy children with the intention of keeping them quiet.

It was the story of a disgustingly good, clean, and disciplined little girl, who wore on her chest the countless medals she had won at school by sucking up to the teacher. Her behaviour caused such admiration that, one day, the king decided to reward her and granted her the rare privilege of visiting the Royal Garden, a paradise where exotic plants grew and piglets ran around. Shortly after entering the garden, the girl discovered that, besides adorable animals, it was also home to an abominable wolf who began to chase her to sink his teeth in her.

The girl fled and hid in the bushes, but since she was shaking, the clinking of the medals gave her away, and the wolf had a feast at her expense.

Is there anyone out there who writes stories like this? If so, please call 415 99 03, adding 93, Barcelona’s prefix.

Upon reading his self-portrait, I thought Arnal Ballester, besides being a great illustrator, was a legendary and courageous man, so I called him to tell him that. As a consequence of that decision, I am here today talking about his book.

I do not know Eugenio Montejo. I do not have his number. Almost everything I have read about him has been written by others. Although coincidentally I have in my library a book by Blas Coll, whom Eduardo Polo, the poet of Chamario, considers his mentor, and which features Montejo as a commentator. As he explains in the book, Blas Coll was a somewhat special typographer. All typographers are known to be somewhat special. Being a typographer is one of those professions that builds character, like being an anaesthetist or a dubbing actor. Mr. Blas wanted to eliminate anything superfluous from language in order to make communication more fluid and rational. In this sense, he thought it was absurd to have very long and hard to pronounce words. Whatever can be said with two syllables should not be said with three. He was surprised, for example, that we needed three syllables to refer to beings as minuscule and short-lived as butterflies, when with one syllable we say ‘sea’ and name the immeasurable.

Mr. Blas Coll wrote down in his Notebook:

Where are we headed with a language that, in a state of utmost danger for the speaker, he must say: s-o-c-o-r-r-o (‘help’)?

When someone shouts such a thing, out at sea, I want to reply from here: let him drown!

Somehow, Eduardo Polo and Blas Coll, neighbours of Puerto Malo, are American relatives of the rhetoric professor Juan de Mairena and his teacher, the poet and philosopher Abel Martín, whose teachings and opinions gave fame to Antonio Machado. What games of scrabble Polo and Coll would have played against Mairena and Martín! What an unbeatable team as contestants in The Alphabet Game! In long evenings which would have become famous they could have travelled the world —and returned to their original position— without moving from the fireplace. As Eugenio Montejo informed us, Mr. Blas had the idea of translating The Aeneid using petroglyphs.

There are unmistakable indications in the writings of his Notebook that Mr. Blas discarded the last bit of the alphabet. Unfortunately, we are only able to read very brief fragments of what may have been the basis of his last years’ delirium. Did he attempt to return to ideographic writing, allowing himself to be lured by the pictorial attraction of the sign?

Certainty, from this point of view, Arnal Ballester is the illustrator who could best understand the peculiarities of Mr. Blas and the various generations of his disciples. Firstly, because he is the author of a book titled I Have No Words. Secondly, because he is a loyal supporter of the letter ‘A’, a letter that every time it is pronounced serves as an homage to another magician-poet-inventor: Joan Brossa; and, because he himself is an A.

Again, Montejo:

Lino Cervantes, the typographer’s apprentice and at times a poet of intimate tones, the colleague who remained the longest in Mr. Blas’ workshop, used to suffer from episodes of unnerving melancholy. He did not survive long, nor did he leave any known descendants, but among his papers the following advice was found to prevent his decay, handwritten by Blas Coll: — In the morning of any day you consider unfavourable, try to concentrate thinking you are simply the letter A. Notice that it is the most joyful and tonic letter of the alphabet. Act under this simple suggestion until bedtime.

The space available to draw on a folding fan is called ‘leaf’. This was at a time when fans were painted by hand, when heat was a more serious matter and there were more flies. In the best era of illustrated books, the space available for drawings was larger than today’s, although there was not such poetic name, as far as I know, to name it. Now we only speak of pages, which is far less charming. Faced with the growing attributions of designers and layout artists, illustrators have lost many of their former privileges.

In the case of Chamario, however, perhaps it would be correct to speak of a leaf, because the book is small and can perfectly be used to fan yourself. Not all books serve as a fan: increasingly so, books have become hefty volumes which are sold by weight. Another advantage of this book’s size is that we can hide it inside another book and read it furtively while pretending to flick through a sports newspaper (adults) or the latest Harry Potter book (children). When we see someone with a huge tome in their hands, we can suspect they are hiding a Chamario in between its pages.

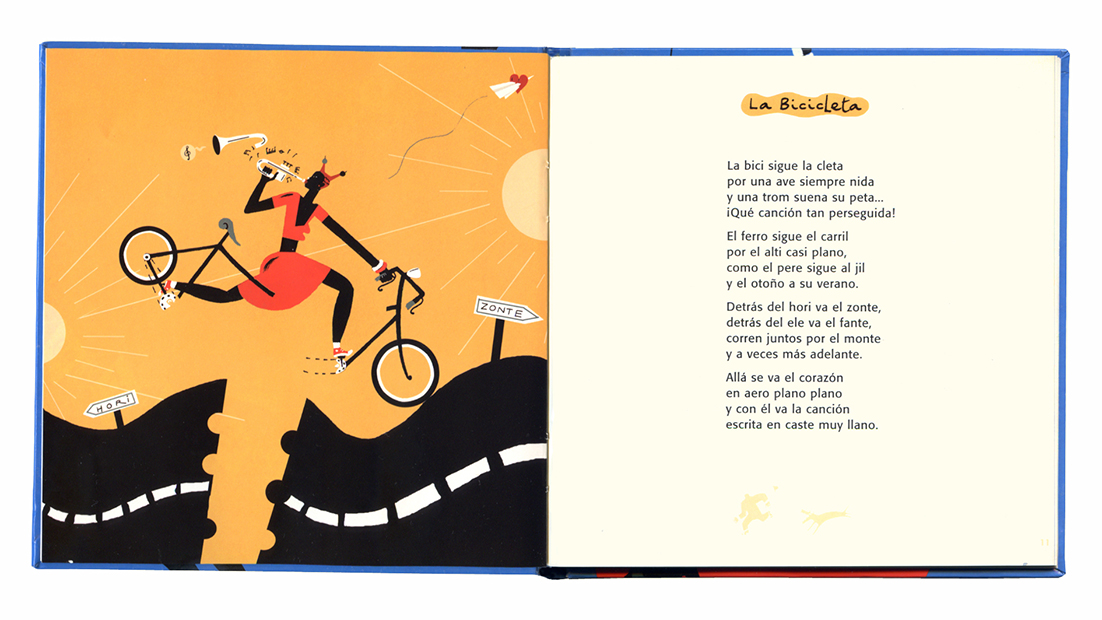

Arnal’s drawings are two-syllable drawings. And it is astonishing all that can be said with such economy of means. Space, in spite of everything, is too restrictive for the characters and there is always someone sticking their leg out of the paper. This, I believe, beyond the aesthetic, commercial, and production reasons that have defined the format, responds to two carefully considered matters. On the one hand, the reader is asked to construct the space that extends beyond the margins. We cannot leave all the work to the illustrator! And, on the other hand, it is faster to draw a leg with a shoe than a whole lady. The economy principle is fundamental for an illustrator, as for all things. Mr. Blas Coll and Eduardo Polo knew this well, the latter also went to great trouble to leave words half-finished. Although his mentor goes a step further. Montejo says:

Mr. Blas attributed the modern success of the press to the growing need to wrap things in paper: Otherwise —he said— one page would be enough to communicate a month’s news in Puerto Malo, and even then there would be many blank spaces left that could well be filled with select pieces of writing.

Some readers could think that Arnal’s drawings, of simple features, have something to do with children’s drawings. Not at all. It is not about approaching a language more familiar to children. Children do not draw like this. If a child is asked to draw a bell, they will first draw a town with all its houses, or with enough of them; then, in the middle, they will draw a church; from the church a tower will emerge; and in the tower’s hole they will hang the bell. If a child is asked to draw a plane, they will need a sheet of paper big enough to fit in the sky, otherwise the plane will not be able to move. And it will need some small wheels to land, because otherwise the plane will have to endlessly fly around in circles and the crew would have to jump out with parachutes. In all fairness, the plane Arnal has drawn for Chamario’s parrot poem has wheels. Which proves once again how unreasonable it is to compare children’s drawings to those of adults. There are always mysterious connections we do not need to understand.

As Juan Ramón Jiménez said, more or less, or if he did not, Arturo Fernández did: ‘If we have not made sense of the world, how can we make sense of a book?’.

The drawings in Chamario are attractive to children because they are so elaborate. They are, so to speak, artifacts with many buttons. Simplicity is not easily achieved, simplicity is not simple to achieve. It is a stripping process, of successive liberations, which needs time and a lot of experimentation. It can be clearly seen in the use of colour: only those who have worked in black and white, and then tried two colours, and then three, can face a box of twenty-four or twenty-four million colours without anguish. Chamario is a book of colours. It seems logical, considering it is a rhyme book, because in the drawings the most perfect rhyme is established by colours.

As a rhyme book illustrator, the highest level of humorism and certainly a Pataphysics title, Arnal’s work is not limited to drawing an elephant when an elephant is mentioned. We must say, in all fairness and although it may seem strange, that this is not usually the case, for which we congratulate Eduardo Polo and thank the publishers for their good choice of illustrator. A great number of illustrators, when illustrating poetry, cast their brain aside with one hand and grab their heart with the other, providing such an excess of sensitivity to the final work that it is necessary to look at it with tinted glasses.

Arnal’s method is different. If he must draw an elephant, he travels to the Land of Elephants. He observes them all and makes a first selection. All elephants have to pass a personality test. The one that starred as Babar in Laurent de Brunhof’s book is discarded. Among the candidates, he chooses the three or four he likes. He invites them to his house for a week. A shared living situation is established. They have breakfast together, they go to the cinema. In the end it becomes clear there is only one elephant —despite everything that is said about elephants’ memory— capable of memorising Eduardo Polo’s verses. Arnal buys the other three a return ticket and stays with the one who has passed all the tests. He draws the elephant in different poses. He buys tons of paper to reproduce the smallest details. A young boy asks his permission to draw by his side and begins to trace Africa’s outline, unbothered, in real size. Arnal, after studying some textures, finally opens Eduardo Polo’s book and finds himself ready to illustrate the poem titled ‘The Hippo’. To draw the hippopotamus, he is inspired by a humidity stain in his bathroom that has a similar shape.

Speaking of elephants and children and books for children, I do not feel it is irrelevant to read the following text, belonging to the forgotten manual of an ignored educator:

A man has the idea of domesticating elephants to use them in wars. A man of the opposing team thinks of shooting the elephants with fire arrows to cause them to panic and turn against their own. In this context, the men of both sides consider that books should be made to educate children. Now, what should these books be like?

I believe it is possible to think about what children’s books should be like, as long as we do not draw too many conclusions, or as long as they are not complete idiocies. Our imagination is already rather poor, in every sense, for us to keep adding barriers to it. Variety and diversity are traits of the world we live in and, although faintly, books should be a reflection of this.

I agree with Arnal in considering children’s books as a laboratory of ideas. They should not solely become learning primers. There are books to learn to read and books to learn to think. We must differentiate them. And we must be aware that the ideal thing would be for our children to learn to read with books that are always interesting and fun. In the golden or pink or blue age of children’s books, writers and artists that worked with children enjoyed great freedom of expression. I would not dare to pinpoint when this age was, or if it ever existed, and I would struggle to explain the reasons for such freedom: perhaps they happened to be aimed at a privileged minority, or perhaps no one was too interested in products for children… It is delicate ground. In any case, I am sure that at different moments and in different countries, sometime somewhere, beloved literary works for children existed, and I am well aware that most of them used verse. I would personally like to find a child who has learned to read with Edward Lear’s limericks.

Nowadays it is not so common to find books such as Lear’s or Chamario, which is why it is fortunate that Ekaré has decided to publish it. And it is fortunate that it exists with Arnal’s illustrations, Irene Savino’s design, and Elena Iribarren’s edition work. The book is a whole, a collective creation where the last person to intervene, and the most important, is the reader who touches it, observes it, holds it, and sniffs its pages. We must open Chamario and stay there for a while.

I would not like to finish —although I would like to do so as soon as possible, since I have dragged this on for long enough— without eulogising rhymers. As a tribute to Eduardo Polo and Arnal Ballester, who have become members of a brotherhood that includes people such as Bécquer, the grand poet of poor rhymes, Gloria Fuertes, the black belt of rhyming, and Javier Krahe, the most unprejudiced lyricist. All three, free and untamable artists, that is, not subjected to poetic rules; all three united by a close bond thanks to the enthusiasm that admirers of rhymers tend to showcase. One begins reading Bécquer and, almost without realising it, becomes entrapped by Krahe. Or vice versa!

There are legions of poets who today consume blank sheets of paper, scattered around the world, and several hundred who regularly publish children’s books, although the genre is not as popular as it used to be. Some of these authors are good poets; others, however, are excellent ones. Yet, few are authentic rhymers. In my opinion, there are seven reasons to choose rhyme over any other poetic art form.

1. Rhyme relates words from the most absurd origins, in a way that seems natural and achieves surprising effects. Antonio Machado rhymes ‘rey’ (king) with ‘buey’ (ox), and without deviating from his verse we have found the following rhymes:

2. Anyone can write a rhyme. Rhymers, more modest than poets, are most likely more honest artists. Poets make fun of rhymers, but rhymers live better and laugh behind their backs.

3. Rhymes can be translated into any language. It always results in something different, because words change, and yet, mysteriously, it always sounds nice. We have Charles Aznavour’s songs to prove it, or this one sung by Nino Bravo, which we cannot imagine being any happier in its original English version.

4. Rhyme has favoured this literary genre, less practiced every day, which is the insult. Without a rhyme, insults are a rather sad thing. Only when combined with a rhyme does it acquire some colour, and also dignifies its author instead of degrading him. In Spanish, Quevedo is a recurrent example. This poem —which is not by Quevedo— was written to criticise Bartolomé Gallardo, a cheeky erudite who had the nasty habit of not returning the books he borrowed.

5. Thanks to rhyme, we notice the graphic component of words, their design. And discover new ways of playing with them.

6. Rhyme is used in most popular poetic forms. It is funny and light, by virtue of its simplicity, and allows the brevity our friend Mr. Blas recommends.

7. Although they may seem to appear out of the blue, rhymes do not avoid thinking, but invite to think. You are left thinking about words, you search for them, wait for them, and all of a sudden rhymes invade your mind. Playing with words, almost without noticing, sad days go by.

We must read Chamario. They are poems for young chums. Also for grown-up chums. Eduardo Polo has thoroughly investigated the DNA of words and shows us how their manipulation mechanism works. Arnal Ballester has found, after many experiments, wonderful graphic equivalents of rhymes. From their work we can fabricate our own toys.

Vicente Ferrer