No tinc paraules (I Have No Words)

I Have No Words by Arnal Ballester is Media Vaca’s first book. It appeared at the end of 1998 in the Books for Children collection along with two other titles. The three books came out of the printers a few weeks before Christmas and we had to rush in order to get them to bookshops.

The decision to publish this book in the first place could be interpreted as a declaration of intent and a desire to depart from established models. However, neither then nor now, eight years later, do I feel comfortable in the role of publisher-executive, and find it hard to speak from that position. I certainly did not become a publisher to give my opinion on the publishing market, although I admit it does get more and more tempting to do so. I became a publisher to release I Have No Words, Noses, Little Owls, Volcanoes, Carrot Hair, and other books that had followed.

When I seriously considered making children’s books (should I say: ‘when I childishly decided to make serious books?’), I remember I drew several lists of possible titles and themes. If there is such a thing as an editorial line, it is based on that list, which is quite similar to Media Vaca’s current catalogue, and which included Aesop, Jules Verne, Agatha Christie, among others. All those lists, written down in a nice notebook, featured Arnal Ballester.

Arnal and I have known each other since 1994. He placed an advert in a magazine looking for a writer who could come up with stories like Saki’s, so I quickly wrote to him stating I was not the right person. More or less. I was enthusiastic about his work and very fond of him. I offered him to make a book in which he could draw all the things he likes to draw. Several times we spoke about the plot, which, as I seem to recall, was initially rather complex. It was gradually resolved and simplified in successive versions in which I did not take part.

The idea to use Frans Masereel’s wordless books as an immediate reference came from Arnal, self-declared admirer of the author of The Idea, Passionate Journey, and The City. In his ‘woodcut novels’ Masereel does not limit himself to linking together actions and movements that are relatively easy to follow, but incorporates psychological elements to achieve, in Herman Hesse’s words, a ‘portrait of human passions’. A remarkable, almost miraculous word, which I now think of associating with the film staging of Lady Windermere’s Fan: the director, Lubitsch, turned Oscar Wilde’s theatrical comedy, full of ingenious quotes, into a delectable silent film.

Arnal Ballester’s other main influence in this book, which he considers most important and which can be detected effortlessly in the entirety of the work, is cinema.

The decision to work with two colours was a previous condition, common to the whole collection and, in general, to all Media Vaca books. It is an aesthetic preference that appeals to a certain graphic tradition, and another, shall we say, moral preference, that has to do with the use of limited resources and saying more with less.

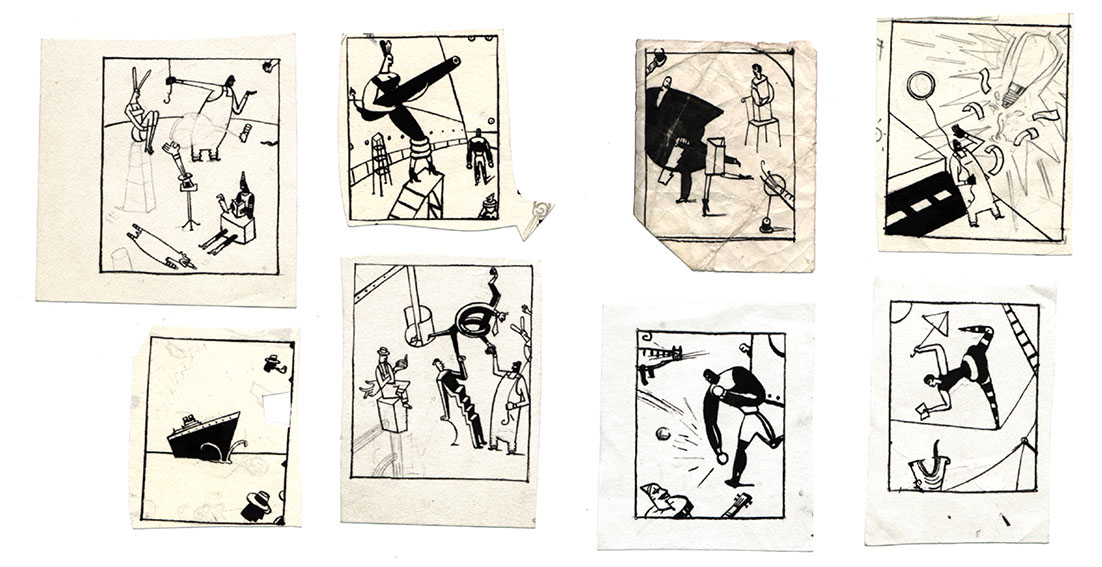

For those who are not familiar with the book, the protagonist of I Have No Words is a character named Rifacli (the name does not feature anywhere in the book and has no relevance, but his name is Rifacli) who, like Ulysses’ apprentice, is dragged into an adventure inside a liner where a circus troupe lives, works, or simply travels. The circus artists perform wonderful numbers which Arnal himself would have liked to see at least once: a fakir who leans on the edge of a giant blade, a boxer who punches back bullets fired from a portable cannon, etc. In this disjointed world there is a mystery Rifacli, and the reader, must solve. When the dull show where dogs paraded in communion frocks was not on, the circus offered acts capable of taking our breath away and leaving us, like this book, literally speechless.

The title No Tinc Paraules means ‘I have no words’ in Catalan. At some point, towards the end of the process, I pointed out to Arnal that a book with a title in Catalan that arrives at a bookshop wrapped in plastic was likely to remain for centuries (that is, three weeks: its lifespan in a bookshop) with the wrapping intact in those places frequented by an audience who does not read Catalan. His answer seemed reasonable. According to Arnal, he had always, from the beginning, referred to the book in Catalan (his family’s language) and if the name were translated it would sound strange to him and would not feel like his own. Besides, it could be written in Swahili, Sanskrit, or Zapotec and nothing would change. If a potential buyer sees a title in another language over an image that captivates him and is not curious enough to unwrap the book and take a peek inside, he would have never been a good reader of the book. Let him buy another one.

Any fool would think —as I did— that a book without words, especially if it is by a wonderful illustrator who applies such rigor to his work, should transcend language barriers and reach the widest possible audience. Oh, what universal ignorance! Turns out everyone in the world who buys children’s books does so to teach them how to read and to make them become doctors, notaries, or anything eminent! And, of course, to read them stories before bed and encourage a pleasant slumber that will turn them into calm and happy people who, for example, would never murder their parents with a chainsaw. Also, evidently, to keep children entertained for a while, the longer the better, so their parents can take a break. (How long does it take to read a wordless book? Five minutes? Two?) Books are also bought so that children learn useful things in life; I have seen books that contain answers to all the questions one could ask oneself over the course of one or a few lifetimes. (But what about books that raise more questions and give no answers? Who would be interested in a book that forces us to make an effort? How will we be able to observe, read, and interpret images if no one teaches us how to do it? Can I like something very much without being sure I fully understand it? What should I think? How can one know if a book is good if it has no text?)

In the worst case scenario, one can always copy the pictures and learn how to draw tigers.

Vicente Ferrer