Why 'Media Vaca'?

What is the origin of Media Vaca and who are its ancestors?

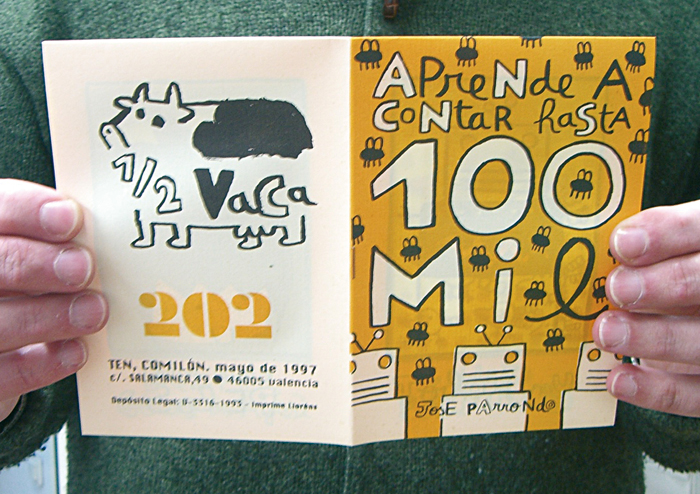

The first three titles of the Books for Children collection appeared in December 1998: I Have No Words, Noses, Little Owls, Volcanoes and Carrot Hair. At the time I had the feeling that I had been preparing for many years to be able to make these books, and yet, I knew nothing about the publishing trade. Since I was fifteen, I have been inventing publications in which I drew, wrote, or selected texts by others. From 1991 onwards I published some booklets —literally a sheet of paper folded twice and stapled in the middle— in which the name ‘1/2 Vaca’ already figured. Except it only showcased the back of the cow, which, by the way, gathers the most fascinating parts: the udders and the fly-swatting tail. We made over three hundred issues of those booklets over ten years, thirty-three per year, in print runs of two hundred copies that were distributed among contributors, subscribers, and friends. Participation was open to everyone. The youngest contributor was one year of age (his parents transcribed the noises he made while bathing with his rubber duck or when he listened to ‘Anchoa y Aceitunas’ by Rossini); the oldest must have been my grandfather, who published his poems using six different pen names (he did not want to be regarded as a hoarder). These booklets featured anything that could fit into eight pages: poems and stories, drawings, newspaper articles, short plays, comic strips, travel logs, lists of things, etc.

Why ‘Media Vaca’?

The name has existed for a long time. It came about in a conversation with Antonio Fernández Molina, author of 1/2 Vaca’s first booklet, which he titled ‘A Dozen Eggs’ and drew on the paper tablecloth of a restaurant. Antonio, who knew my reluctance to explain the origin of the name —I never know what to answer—, has spared me the trouble by providing his own version in a volume of memoirs: Fragmentos de realidades y sombras, p. 100. Aragon’s Library of Culture, Zaragoza, 2003.

What has Media Vaca inherited from Vicente Ferrer’s experience as an independent publisher?

For many years I participated in independent publishers’ meetings, especially those held in Huelva under the inspiration and coordination of Uberto Stábile. I remember that every year there was a debate among the attendees on the same subject: ‘What does it mean to be independent?’. I am not sure whether I can be considered an independent publisher only because I have talked so much about it and featured in exhibitions and meetings under that slogan. Maybe so. Am I now? I do not know. I suppose what matters is finding the path that will allow you to work doing what you like and be able to make decisions. It is not always a question of money, but as Ramón Gómez de la Serna asked of his publishers, it is a fundamental requirement to ‘be bold and open to new things’. Rather than independent publications, I would say there are people who have a greater tendency to not follow rules and act according to their own criteria. At those meetings I met very notable personalities: people who work with rigor, have fun, and make their enthusiasm contagious.

What criteria do you apply when choosing either a contemporary or a classic author and pairing them with a particular illustrator? Do you first think of the text or the illustrator?

Although the presence of illustration is very important in Media Vaca’s books, and perhaps this is the feature that most characterises them, in reality many of them are based on a pre-existing text. At the origin of every book there is another book: a book in my library, which is an old friend. I decide to edit a book after giving it much thought, and only when I already have in mind the illustrator who could illustrate it. This specific person and not another. I am an illustrator myself, and mainly work with illustrator friends whose careers I know well and with whom I share passions and professional concerns.

Why publish a book that already exists?

I am not interested in publishing a book that already exists, unless we were to do something different with it. One can cook many different dishes with the same ingredients. It would also be inaccurate to identify novel and book. A book is a sum of things, not just a written text. The typography, the illustrations, the margins, the choice of paper, the format, the binding, the weight, the manageability, and even the smell of paper and the ink are important.

Why do you choose to publish in an unusual format?

Most children’s books published in Spain are still pocket editions, a format which reduces production costs but does not respect the reproduction of images very much. When I was debating the format issue, I thought I was only going to have to make the decision once, since my intention was to give all books the same characteristics. On the one hand, to make them stand out; on the other, so they could have a similar price point: I wanted all the books to have the same possibilities in some way and not compete with each other. I did not select the format according to the size of the sheets, although it was important that no paper would be wasted. In fact, the paper is made to measure and this is a special difficulty I did not consider enough. The 18,5 x 23 format existed before I used it; my model was a book from the German publishing house Taschen, which, by the way, carries out long print runs of their titles and for whom custom-made paper is not a problem.

What is the importance of typography in the composition of a book for children (and the not-so-children)?

Finding the right typography in an early stage favours the work. Typography represents the writer’s voice. To offer an approximate idea of its importance, it is enough to imagine what the voice of an actor means in a film. It is another aspect to take into account when working to confection a book, and also —especially— in children’s books. The text itself —let us not forget— is a drawing.

In so-called children’s literature, which sometimes offers such disparate products, the practically only criteria applied in regards to typography is that of legibility. Many times we have seen books with fonts that are large and perfectly clear while the texts are perfectly confusing if not idiotic. To read nonsense more easily, is that an advantage? It gives the impression that a clean and round font can make an unfortunate text more digestible precisely because of its ‘childish’ appearance, when it is not at all a recommended reading for any reader. What readability are we talking about then? I personally like drawings in books (in theory, in any book) and large fonts. If a font is nice and we like it, why make it invisible by offering it in a body so small its features cannot be appreciated?

What is your work process with the illustrator? Could you explain the stages of your collaboration and the most fascinating part of its evolution?

The relationship with illustrators is essential to carry out the work in good terms and it is usually tight, especially during the first stage of the process. I previously carry out research work around the text by searching, if there are any, other contemporary or old editions, and versions in other languages from other countries.

I also gather all the graphic material which I consider to have any relation with the theme, listening to my intention and the memory of past readings. Landscapes by Cezanne and Van Gogh for the sceneries of Carrot Hair, drawings and handwritings by Fernand Léger for Panama and the Adventures of My Seven Uncles, popular aucas and engravings for The World Turned Upside Down, etc. At this point I am exhaustive; if possible, I want to become familiar with the previous editions of the book (sometimes it is difficult to find out of print books that must be tracked in libraries and second-hand bookshops). With all the material at hand the illustrator and I sit down to converse and start discussing our points of view. When the illustrators draws his or her first sketches, we try to settle on a definite first drawing which will be what sets the tone for the collection. Finding the right tone is without a doubt the most important step, which allows to begin the journey.

Assembling the book is almost always the last stage of a long work process, although in occasions we have to draw an outline before: drawing outside the text in double-page spreads, one drawing per page, change of ink according to the paper, etc. In general, it all assembles like a puzzle that fits without missing a piece or having too many.

How long does it take to make one of your books?

We never know. It depends on many things. For example, on the illustrator’s availability, speed, or perfectionism, on the complexity of the project and, well, on all types of factors, such as whether the day is cloudy or sunny. The book Panama and The Adventures of My Seven Uncles by Blaise Cendrars and Fabio Zimbres has the top spot at the moment. It took six years from the moment when I commissioned the illustrator the work, after having advanced the arrangements with the heirs. In this case, distance complicated the work immensely: Cendrar’s heir lived in a town outside Paris, the illustrator in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and the translator in Malaga. We would send the Spanish text from Valencia, which the translator would send back by letter, and Ms. Cendrars would send it via fax to one of her friends in Chile to ask her opinion. The illustrator sent us samples of his drawings by e-mail and we met in Porto Alegre on various occasions. Amidst all this coming and going of drawings and poems around the world, Fabio restarted his work at least twice until he found the tone he wanted to give his illustrations.

Which is the most complex book you have published so far? (And why, of course.)

I have had so many obstacles while pushing forward some projects that I would rather believe that from now on I will only make easy books. I love how it sounds, ‘easy books’. However, I still do not know what that means. When I have tried to make an easy book I have failed miserably. A good example is Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. Lewis Carroll’s text is copyright free and the heirs of the illustrator, Franciszka Themerson, are happy for us to make the book. Now, the translation into Spanish is very complicated, and after considering no less than seven or eight different versions among those available, I do not think any of them are an entirely satisfying option. Offering the book to a new translator does not guarantee a better result. We have even considered publishing the book in English. It is possible, but where will we sell it? We have contacted and tried to convince international distributors, but illustrated books are not a profitable market for export, unlike design, architecture, or photography books, so no one is showing great enthusiasm. On the other hand, Franciszka Themerson drew the pictures in London during the Second World War. From her house she could hear the bombs dropping, so she decided to begin this work to distract herself from the chaos outside, not knowing if they would see the light one day. The book was not published during the artist’s lifetime, and only a limited collector’s edition was made in recent years. Some drawings have been lost and would have to be replaced, but how? After several years I am still thinking about it, and I have come to the conclusion that this ‘easy book’ is not so easy after all.

Media Vaca has an artisanal feel and recovers a style that has more to do with what was being made in the 1930s than today. What does this tradition mean and why do you believe most of it has been lost?

That artisanal feel possibly comes from working with two inks, which is not very common these days. This decision was not made to reduce costs, but to respond to an aesthetic preference that appeals to a certain graphic tradition. To put it pretentiously, I try to follow the lessons of my classics. Many machines today are prepared to print in CMYK, and the use of direct inks sometimes complicates the process rather than simplifying it. I believe that improving the technique does not necessarily boost creativity, and would even be inclined to say that in many cases the opposite occurs. In my opinion, the loss of this tradition has to do with: 1, lack of information; 2, searching for greater economic profit; and 3, maintaining certain trends. How is it that at a time when the most advanced technology is available all products look so similar? The lack of information could be solved by teaching the history of art and the history of books to students and readers; customers would become more demanding and choose better books if they knew that they could be made in a different way. Similarly, illustrators would not look at models from yesterday’s or today’s market; in addition to Tim Burton, they would notice Edward Gorey, Charles Addams, or Edward Lear, and discover that there is much to learn from Kubin, Goya, and Bosch.

What do you think is the most important part of the editing process?

The most important part of the editing process is the entire editing process. To take care of every detail. To not mke seriuos speling mistaakes. As well as surviving the editing process, which requires special acuity and tension. And, of course, before starting the editing process, to have the desired book already perfectly defined. There is no use thinking about colour or the paper or the cover design if one does not know in what direction they are going. During the process there are many decisions to be made; the more information we have on the book we want to make, the more solutions will naturally be imposed.

Do distributors understand what and who Media Vaca is and do they put you within reach of readers in bookshops?

A few years ago, when we were starting out, I was asked that same question and this is what I answered: ‘The books are slowly being distributed and can be found in more and more bookshops and cities, and although they occupy the most discreet shelves of the children’s section, anyone who is interested can approach them and check them out’. Now I could not say the same. The books are being distributed, for many reasons, more irregularly than before. Some experts have realised we do not exactly make books for children, and the market, which adores novelties, no longer deem us novel and is unsure of what to do with projects that are not easily classified. What really works is people’s recommendations: a reader talking about the books with another friend.

What do you think are the weak spots of the Spanish editorial system and what is the current situation?

My opinion on this matter is only another opinion. What I understand by weak spots is what allows many publishing houses to survive. Overproduction is a problem, evidently, but in a market in which only novelties compete, it seems inevitable that this will keep happening. The issue is complex and deserves to be expanded upon. In fact, it is discussed so widely in other places that there is no room for anything else. It is a prickly subject, because no one assumes responsibility: publishers accuse distributors and booksellers (and even authors); distributors accuse booksellers and publishers; booksellers accuse distributors and publishers; and everyone, with no exception, accuse readers for their lack of interest and public administrations for their lack of support. This reality hides more grave shortcomings: many of the many published books are bad books that no one cares about. Books that convey little love, but which demand an immediate return of investment. Some publishers see their catalogue as a herd of cows, ready to be milked. If only, when they milk them, they knew how to sing to them and call them by their names!

If you can sustain a publishing house with only three books a year, what is the cause of the increasingly concerning over-saturation of the publishing market?

The publishing house is maintained because there is only one person running it full-time. And, fortunately, that person, although whimsical, does not have expensive taste. We do not produce more than three books a year because we do not have the administrative or economic capacity to do so, but if we did, we would not make more books either. Why? Because time is needed to take care of projects, because each book should be dedicated the effort it requires, and because, in all honesty, I believe not many books are worth devoting the time that is becoming more valuable every day.

What countries are references in the world of illustration? Where is Media Vaca’s work most appreciated? Are there similar experiences in Spain and abroad? What do you share with them and how are you different?

In my opinion, the countries that pay most attention to children’s books (which probably account for 90 per cent of illustration work) are the United States, France, and Japan. Let us say that these are the countries where the authors and publishers that I am most interested in are found. Korea is an important market, but not so much for its innovative and creative aspects: they are big consumers of foreign books. England has produced the great classics of the genre, and yet it currently offers the dullest products, destined for mass consumption. German books have also seen better days; I think their books have become very conservative and have lost much of their surprise capacity.

Our books are known outside Spain especially due to the two awards from Bologna Book Fair in 2002. It was the first time a Spanish publishing house had received this award, and the first time in the Fair’s history that a publishing house had won the first place in both categories: Fiction (Mr. Korbes and Other Stories by the Brothers Grimm) and Non Fiction (A Season in Calcutta). Despite the significance and prestige of the award (competing with an approximate of a thousand titles from over 20 countries), the event had no repercussion in Spain and the first edition of both books (3,000 copies) has not yet sold out.

Similar experiences? There are no doubt publishing houses with which I share some things, at least some illustrators. Other proposals, however, which seemed close to ours, happened to be the exact opposite, or at least that is how I see it: camouflaged businesses where the most outstanding work of an artist and a hardcover binding are nothing but attractive decoys to lure in a new market. When we began travelling and visiting fairs, I was looking for books that were similar to what I wanted to do. Now at fairs I look for publishers with good conversation, even if their books do not resemble my own. I see myself, however, in many books by Petra Editions, from Zapopan, Mexico, or by Benoît Jacques Books from Paris, or by Baobab from Prague, or by Parol-Sha from Tokyo, or the booklets Armin Abmeier publishes in Germany under the Die Tollen Hefte imprint.

What books will you never make?

I wrote somewhere: ‘When we began planning this collection, we found it easier to agree on which books did not interest us in the slightest: firstly, those which are poorly written and illustrated; secondly, those which treat children as if they are fools; thirdly, those which exist a million times (Little Red Riding Hood!); fourthly, those which respond to a trend; fifthly, poorly edited books that are not made to last; and lastly, those which have renounced poetry and mystery’. However, this year we have published a book —rather, twenty-one books in one— dedicated to Little Red Riding Hood, so you never know. I can assure you, though, that I would not begin a bidding war to get my hands on the publishing rights of a famous author. I recently tried to find out information on the publication conditions of a book I liked and found myself neck-deep in an auction where the publisher who most took care of its catalogue was never going to win, but instead whomever was willing to offer the highest amount. What an unfortunate experience!

I have read that Media Vaca aims to be a library. What do you deem essential in a good library and what milestones have you already achieved with yours? What possible or impossible dreams do you still want to fulfill?

Every reader is a library, and I do not believe there is anything essential. There are readers for all tastes and, luckily, the same reader can perfectly be a fan of Dostojevski and a marine plankton enthusiast. My desire is to finish the books I started long ago. Among them, Alice by Franciszka Themerson, the third and final edition of the dictionary of favourite words My First 80,000 Words, which will include 333 authors, and other books by Artur Heras, Micharmut, Ajubel, Alfredo, Pablo Amargo, and El Persa. Oh, and one dedicated exclusively to children’s drawings.

Vicente Ferrer

Image: Learn to Count to a 100 Thousand, by José Parrondo: booklet no. 202 of the 1/2 Vaca collection (May 1997). Photograph by Ingrid Santos.