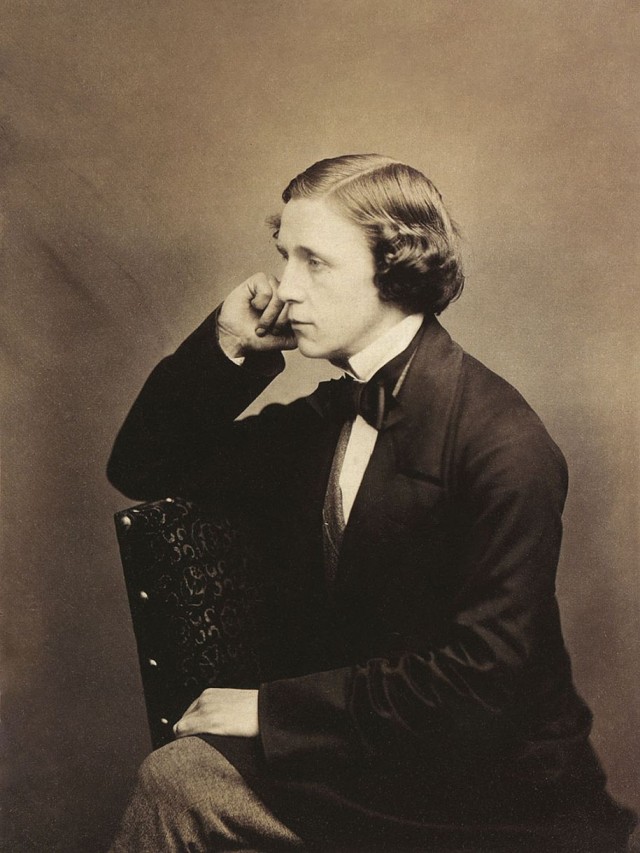

Carroll, Lewis

Lewis Carroll is the pen name of the creator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; his real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. The pseudonym was constructed from his two given names: Charles-Carroll and Lutwidge-Lewis (he first translated them into Latin: Carolus and Ludovico; he reversed their order; and translated them back into English; Lewis and Carroll). Lewis Carroll was, in fact, his alter ego; a tamer of snakes and toads, a conjurer (birlibirloque), a brilliant editor and illustrator of children’s magazines, left-handed (as his two sisters and eight brothers), an insomniac, deaf in one ear, inventor of games, of useless devices, of puzzles, a passionate collector of bicycles and tricycles, creator of word plays and his own languages. His passion: inversions, like writing letters beginning with the signature and ending with the name of the recipient, like writing texts to be read with the aid of a mirror, since they work in reverse and upright: ‘It is a poor sort of memory that only works backwards’, stated Carroll.

Lewis Carroll was born in Daresbury (Cheshire) in 1832 and died in 1898, fallen victim to one of the wind drafts he always tried to avoid in life. Son of a protestant pastor. He lived for forty-seven years at the University of Oxford, first as a student and then as a professor of Mathematics and Logic. A man of a calm, chaste life. British bourgeois of the second half of the 19th century, in the middle of the industrial era. Strict deacon of the Church of England. Haughty, introverted, stubborn, bored in classes and meetings. ‘Reverend Dodgson’, as he was known in his public life, remained single. Neat, romantic, puritan, of a distinctive asexual life. His weaknesses: puppets, theatre, and opera. Excellent photographer, especially of young clothed and nude girls. Poet and storyteller. His slight stutter prevented him from preaching; he comfortably stuttered (as his two sisters and eight brothers). In Diary, he speaks of his upmost failure as a teacher and about his friendship with many children, especially with girls between the ages of eight and fourteen, whom he describes meticulously, listing them in alphabetical order, and of whom he expresses his fascination in a photograph collection compiled and published under the title Girls, composed with talent and artistic sense. He never photographed boys, since he thought nudity did not suit them and they reminded him of his dark school days.

Alice, Magdalem, Katie, Lorina, Agnés, all of them were muses, pre-pubescent angels —particularly Alice Liddell— of the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. He observed them in the streets, in public gardens, he looked for them in reunions and parties and, especially, in children’s theatres in London. He chose them perfectly from among the daughters of his Oxford colleagues or he turned to more humble and less strict families. The timid mathematics professor was capable of the most daring things to gain a little girl’s friendship.

On the soft and bright afternoon of Friday 4 July 1862, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, teacher of mathematics in Christ Church, Oxford, relates in his Diary one of the first encounters with the daughters of Christ Church’s Dean, a well-known author of Liddell & Scott Greek Lexicon:

‘Atkinson brought over to my rooms some friends of his, a Mrs. and Miss Peters, of whom I took photographs, and who afterwards looked over my albums and staid to lunch. They then went off to the Museum, and Duckworth and I made an expedition up the river to Godstow with the three Liddells; we had tea on the bank there, and did not reach Christ Church again till quarter past eight, when we took them to my rooms to see my collection of micro photographs, and restored them to the Deanery just before nine’.

Those three girls were Lorina, Edith, and Alice Liddell, who was barely ten at the time.

Since then, many constant references about meetings, trips to the countryside, games and celebrations are found in the Diary featuring these three muses. On holidays they used to visit the reverend to enjoy his stories and interpretations. We can image Carroll transformed into a kind of master of ceremonies or a Bluebeard, with a briefcase full of dolls and toys to charm his young visitors.

On one of those innocent walks in the countryside, where Carroll told many and varied stories, a powerful story suddenly appeared. It was so spontaneous, entertaining, fluid, and masterfully constructed that it seemed dictated by a spirit who had possessed the narrator. Apparently, one of the companions who was listening to this story said, astonished: ‘I rowed stroke and he rowed bow… and the story was actually composed over my shoulder to the benefit of Alice Liddell, who acted as the cox of our gig. I remember turning round and saying, “Dodgson, is this an extempore romance of yours?” And he replied, “Yes, I am inventing as we go along”’.

Alice then asked Carroll to write it for her, something she had never done before, and to which the narrator did not give much importance. However, it was not long until he satisfied his favourite muse, as can be read on his Diary entry from 13 November: ‘Began writing a fairytale for Alice. I hope to finish it by Christmas’.

We know the story was finished on 10 February 1863, and that the masterful task of illustrating it relied on John Tenniel. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland would be published in 1865 by MacMillan Publishers. The story begins with a memorable scene for Carroll and his young friends: ‘Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversation?”’.

Carroll, then, became a professional writer due to a very particular request. His accomplice audience, at first, were children, he not only felt trusting and had certain intimacy with them, but he also felt completely free of malicious criticism and censorship. His ideal readers were children, members of his personal creation workshop. This is why he deeply respected their answers, impressions and comments. He thought of ways to be left alone —without adults— with his young confidants for a very valid reason, revealed in one of his letters to his mother: ‘Would you be able to tell me if I can count with your girls to invite them over for tea or dinner? I know of cases where they can only be invited in groups, and such friendships are not worth keeping. I do not think that someone who has only seen the girls in the company of their mothers and sisters can know their nature'.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to track the countless allusions made to Carroll’s friends in the book about Alice. Numerous hypothesis, which will never fail to be so, have been created to explain the origin of the characters and events of the adventures of little Alice. What we can be sure of, however, is that the author’s imaginative quarry cannot be conceived without the universe that constituted his frequent meetings with the Liddell girls. When he told them a story he would always address a girl in particular. His strategy was very simple and ingenious: he encouraged lively conversations and question games between the girls, from which he took seeds of ideas that served to ‘build bridges’ between one another. In this way, the stories were developed with the collaboration of the whole group, which gave the participants great satisfaction.

At some point we should highlight Carroll’s timid and elusive nature in terms of his social and editorial recognition. And, although it may seem strange to many, Dodgson detested celebrity. Writing was not his biggest ambition, on the contrary, it was his way of being alone. Which is why he rejected every publishing offer. He never wanted to be recognised on the streets: ‘Nothing would be more unpleasant for me, than to have my face known to strangers’. He also did not want to establish communication with any press media. Famous is the anecdote that tells how he returned correspondence with the observation ‘Unknown’.

But time had another fate in mind for Carroll. Contrary to his wishes, and thanks to the spontaneous idea of Alice Liddell, the elusive narrator achieved worldwide fame. As it usually happens with masterpieces, the reception of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was varied: Illustrated London News and The Pall Mall Gazette gave it a warm welcome; The Spectator recognised its value, although condemned the ‘mad tea party’; Athenaeum thought it was a forced and gruesome story; and The Illustrated Times recognised the author’s wit, but stated that Alice’s Adventures were ‘too extravagantly absurd to produce more diversion than disappointment and irritation’.

Carroll’s dexterity goes beyond his tales, as we have seen in excerpts from his Diary and his letters. Therefore, the immediate —and permanent— welcome that the books about Alice received was not gratuitous. Parallel to the creation of Alice, Carroll took notes in his Diary about his work: ‘It has been so frightfully hot here that I have been almost too weak to hold a pen, and even if I had been able, there was no ink — it had all evaporated into a cloud of black steam, and in that state it has been floating about the room inking the walls and ceiling till they are hardly fit to be seen: today it is cooler, and a little has come back into the ink-bottle in the form of black snow’. With certainty, most of the masterful stories Carroll told his girls were lost in time and forgotten by his audience. However, fame played a nasty trick on him, since his books’ recognition continued to grow.

When one enters the world of Alice one finds extraordinary events and characters in the midst of anarchy to which we will always try to give meaning and balance. In both stories the game is the primary mechanism through which one attempts to restore said order. The basic structure of Through The Looking-Glass, for example, is based on chess, while the Queen of Hearts’ favorite game is croquet, games that Alice knows. That is to say, she knows the rules, understands how they work and, therefore, can be ‘competent’. It also means we can join the dialogue to logically construct a reasoning.

Chaos, anarchy, and incompetence are at odds with the game. Playing croquet with hedgehogs, flamingos, and soldiers, instead of the conventional hoops, balls, and nets, is conceivable as long as they try to imitate the behavior of the implements. However, in Wonderland, characters behave capriciously, making the game a real folly.

While in Wonderland the reader enters an entirely anarchic world in which everyone acts as they please and it impossible to reach an agreement, in Through The Looking-Glass, the reader is faced with a rigidly established world, with no space for free will or autonomy. Tweedledum and Tweedledee, the Lion and the Unicorn, the White and Red Knight must fight at regular intervals without considering their emotions.

In the first book, Alice enters the adaptation game in a lawless world; in the second, she enters a world governed by laws that oppose her, subverting logic and forcing her to accept the impossible. For example, she has to learn how to get away from a place to reach it, or how to sprint to remain where she is. In Wonderland she is the only character who keeps control. In Through The Looking-Glass, the only one who passes rational tests.

In any case, Carroll challenges the reader by introducing them, alongside Alice, to the ‘other side’ of language and reality. According to Gilles Deleuze: ‘Carroll’s work has everything required to please modern readers: children’s books or, rather, books for little girls; splendidly bizarre and esoteric words; grids, codes and decodings; drawings and photographs; a profound psychoanalytic content; and an exemplary logical and linguistic formalism. Over and above the immediate pleasure, though, there is something else, a play of sense and nonsense, a chaos-cosmos’. (Deleuze, 1969)

What is surprising about Alice books is that, despite the passage of time, they continue to offer readers and writers a modern, advanced and fresh approach to manage language, the main protagonist of his stories. Little Alice swims in words, reaching the core of their meaning: she goes through them, breaks them down, wears them, takes them off, eats them. Words and things come to life and have their own reason in the world of Alice: ‘“What is the use of their having names, if they will not answer to them?” “No use to them,” said Alice; “but it is useful to the people that name them, I suppose. If not, why do things have names at all?”’. (Through The Looking-Glass.)

According to W. H. Auden:

‘There are good books which are only for adults. There are no good books which are only for children. A child who had enjoyed the Alice books, will continue to enjoy them when they grow up, although the meaning of their reading will most likely change. When one reflects on children’s books, one immediately gets the idea of how the world is offered to them, and how it relates to the young reader’s reality. According to Lewis Carroll, what a child desires above anything else, is for the world they are in to make sense. It is not orders and prohibitions as such, imposed by adults, what the child rejects, but above all the fact they no law can be found that links orders to each other, according to a consistent pattern’. (Auden, 1962)

Lewis Carroll split the history of children’s literature in two: after Alice no one accepts a stiff, artificial, mellow, or shamelessly didactic book. No one would dare to negate the powerful appeal that Alice has for children and adults alike. It is also difficult to think of a great author from last century who has not written about Carroll and his books; the list includes W. H. Auden, Max Beerbohm, Kenneth Burke, G. K. Chesterton, John Ciardi, Walter de la Mare, William Empson, Robert Graves, James Joyce, Harry Levin, Vladimir Nabokov, Joyce Carol Oates, J. B. Priestley, V. S. Pritchett, Saki, Allen Tate, Edmund Wilson, Virginia Woolf and Alexander Woolcott. Leonard Bernstein raised his children on Alice books, which have also inspired Deems Taylor and David del Tredici, among other composers.

Lewis Carroll will always be a mysterious author. Carroll, alter ego of the nervous, neurotic and eccentric Reverend Charles L. Dodgson, is a complex writer whose work offers the critic like an endless source of meaning. The impressive richness of his language, the perfect architecture of his stories, and the impact he causes on the reader make Lewis Carroll an archetype of modern man and his paradoxes, a classic writer and a permanent contemporary.

To blur boundaries, establish new codes, make dreams visible in order to offer them to our eyes, would be some of the metaphysical tasks to which Carroll dedicated his life. Only a person addicted to the avant-garde, to novelty, could embody this metaphor.

We must see in Lewis Carroll his advanced character. With him, contemporary letters acquire pose, fluency, and drive of their own. It would be impossible to think of Wittengstein, Cortázar, or Calvino today without the polymorphic writing of this modest clergyman. His unprejudiced word turns into a verbal record for those who seek to restore the ‘utopian function of language’, the plenary freedom of poetic creation.

Jorge Cadavid